Theories

Overview

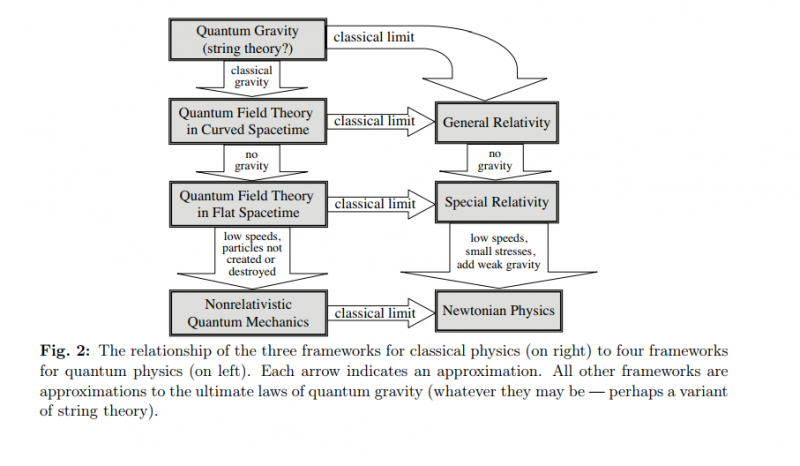

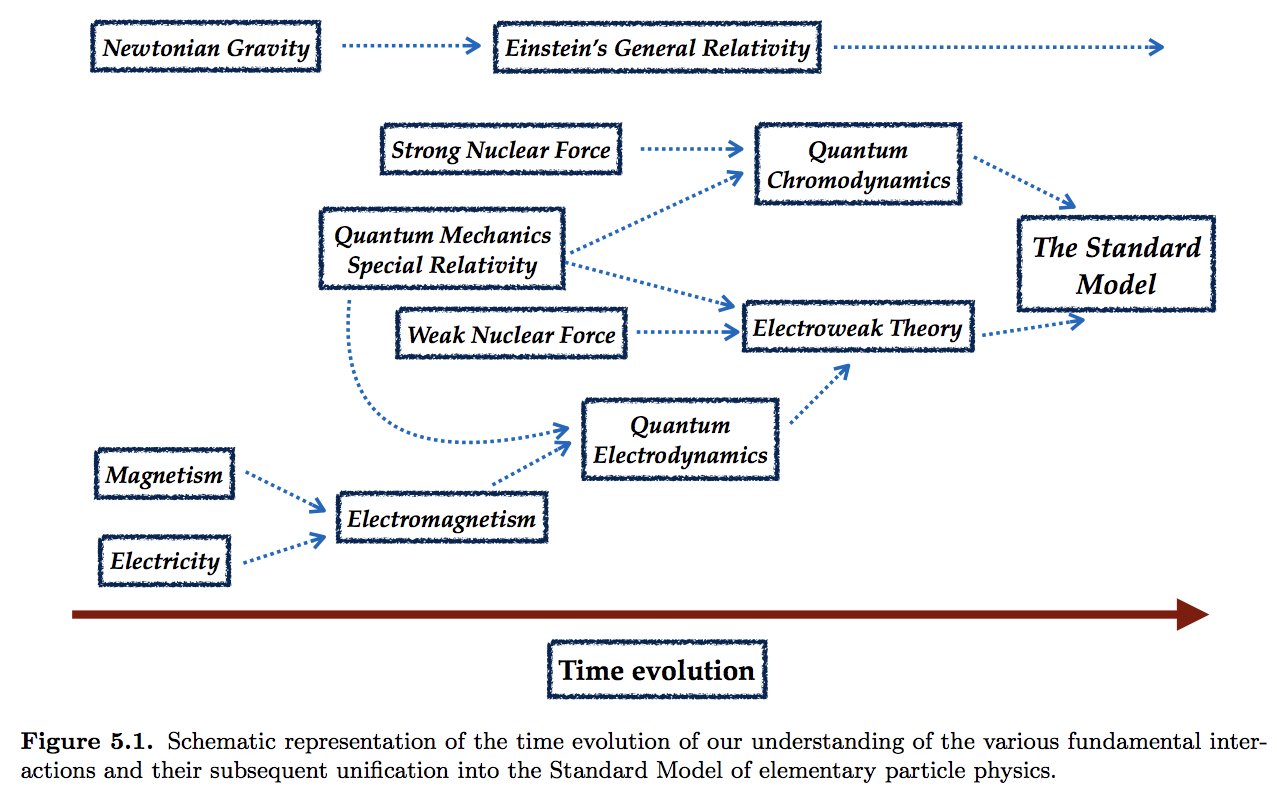

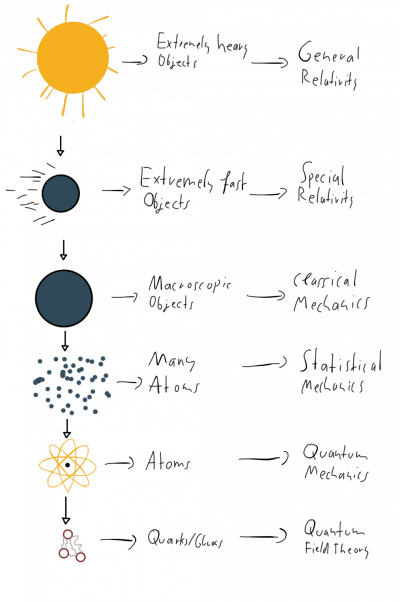

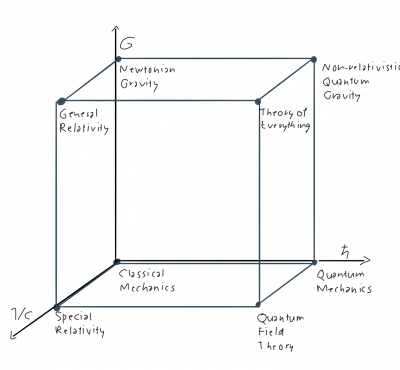

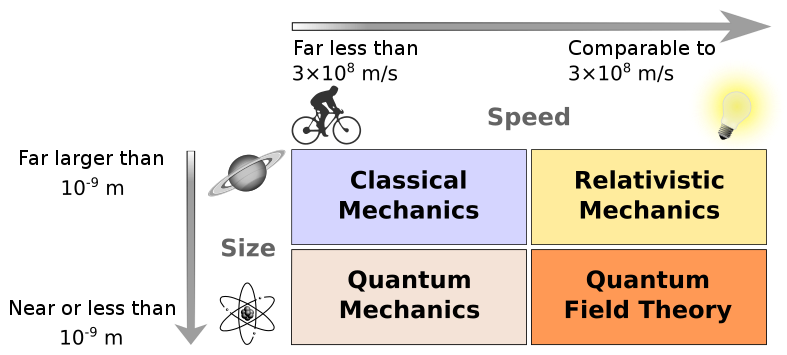

There are various theories that provide good approximations to nature at different scales. Newtonian mechanics describes the behaviour of macroscopic objects reasonable well, while quantum field theory is the best theory of elementary particles that we currently have. On the other hand, we have general relativity which works perfectly at astronomical scales. It is commonly believed that to describe nature at even tinier scales than we can currently probe, a new theory is needed that merges general relativity with the principle of quantum field theory. This hypothetical theory, which has not been found so far is called quantum gravity. There are several proposed theories of quantum gravity, but none of them has been experimentally confirmed so far.

Classical mechanics describes everyday physics and can be described by using everyday space, configuration space, phase space or Hilbert space1). Classical mechanics works perfectly for phenomena like billiard-ball collisions. However, we can ask what happens if we make the billiard balls smaller and smaller? What if we scale the whole system down by a factor 10, a factor 1000, or even a factor 10000? Will the laws of classical mechanics still hold?

In principle this could be since the $m$ in Newton's second law does not come with a predefined allowed mass range, say 0.1 kg up to 10000 kg. But the correct answer is no. If we make things smaller and smaller we eventually end up in a regime where the laws of classical mechanics no longer apply. The scale where this happens is encoded in Planck's constant $\hbar$. If we are dealing with systems where the action is much larger than $\hbar$ we can treat it using classical mechanics. Effectively this means that we set $\hbar$ to zero. If the action of the system is close to $\hbar$ we need to take quantum effects into account.

The crucial difference between classical and quantum mechanics is that the algebra for observables is non-commutative, as encoded in Heisenberg's uncertainty principle2). Apart from this difference, we can again use everyday space, configuration space, phase space or Hilbert space3). The question why we need to change our "naive" algebra to a non-commutative one is the what discussions about the interpretation of quantum mechanics are all about. The procedure where we start with a classical theory an construct the corresponding quantum theory is known as quantization.

Another instance where classical mechanics becomes invalid is when our objects move at speeds close to the speed of light $c$. In such systems, the correct theory is special relativity. The difference between special relativity and classical mechanics is that we now use Minkowski space instead of our everyday Euclidean space. Again we can equivalently use the corresponding configuration space, phase space or a Hilbert space. When the objects in our system move so slowly that we can treat effectively $c$ as infinity, we can use classical mechanics.

Next, when we are dealing with tiny objects that move at speeds close to the speed of light, both, quantum mechanics and special relativity, fail. If we combine the lessons learned in quantum mechanics and special relativity properly we end up with quantum field theory. Here the fields obey a non-commutative algebra and it is conventional to describe quantum fields either in Hilbert space or configuration space4). The Hilbert or configuration space in interacting quantum field theory is more complicated since the particles described by quantum fields can have an internal structure and this internal structure becomes important when fields interact5). Hence our physics not only happens in spacetime but also in internal spaces. The theory that deals with physics in internal space is known as gauge theory. The appropriate geometrical tool to describe physics in spacetime and internal spaces at the same time are fiber bundles.

Next, when we are dealing with tiny objects that move at speeds close to the speed of light, both, quantum mechanics and special relativity, fail. If we combine the lessons learned in quantum mechanics and special relativity properly we end up with quantum field theory. Here the fields obey a non-commutative algebra and it is conventional to describe quantum fields either in Hilbert space or configuration space4). The Hilbert or configuration space in interacting quantum field theory is more complicated since the particles described by quantum fields can have an internal structure and this internal structure becomes important when fields interact5). Hence our physics not only happens in spacetime but also in internal spaces. The theory that deals with physics in internal space is known as gauge theory. The appropriate geometrical tool to describe physics in spacetime and internal spaces at the same time are fiber bundles.

A third instance where classical mechanics fails is in systems where gravity is strong6). In such systems, the correct theory is Einstein's general relativity. Here the Minkowski space of special relativity becomes replaced with a more general Lorentzian manifold. Hence spacetime only looks locally like Minkowksi space and is otherwise curved.

So far, there is no theory that works for systems with strong gravity and tiny objects that move close to the speed of light. The hypothetical theory that combines the lessons of general relativity and quantum field theory is known as quantum gravity.

- Further Diagrams that explain the relationship between the theories

-

Image by GYassineMrabet published under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Image by GYassineMrabet published under a CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)], via Wikimedia Commons

Field Theories vs. Particle Theories

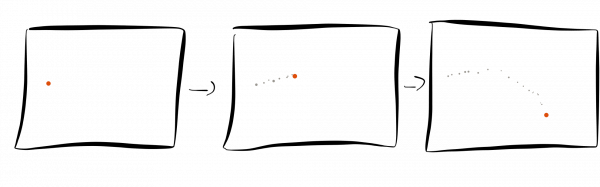

In a particle theory, the solutions describe particle trajectories:

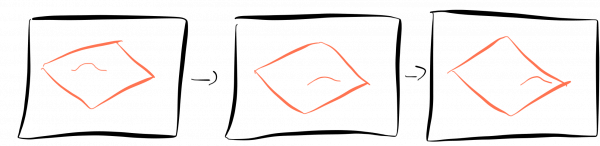

while in a field theory the solutions describe sequences of field configurations:

However, take note that we can also describe particles in field theory. A particle in quantum field theory is interpreted as a field excitation. When, for example, every electron is an excitation of the same electron field, we can undertand why every electron that we observed so far looked exactly the same.

Field theories have the further big advantage that they treat time and space on an equal footing, which is necessary because of special relativity. In contrast, in a particle theory, we always use the location as a function of time $q=q(t)$ to describe the particles in question. A field $\Phi$ is a function of space and time $\Phi(x,t)$.

Another advantage is that field theories are much better suited if we are dealing with systems where particles disappear and different particle appear instead since we can use the field as a bookkeeping device. Formulated differently, a field is a much better tool to keep track of particle appearances and disappearances than a description in terms of individual trajectories.

Despite all this, the question remains: What is more fundamental, particles or fields?

If we look close enough our detectors always see particles and not fields. Hence some people7) argue that only particles are real and fields are merely convenient calculation devices, similar to the wave function in quantum mechanics8).

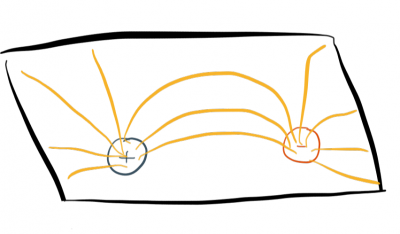

In the conventional interpretation, charged particles are sources for fields. However, it is also possible to imagine that fields are the sources of particles9). Namely, when there is a wormhole in spacetime the field lines flowing in and out of the wormhole look like those of a particle-antiparticle pair.

One view: Source is primary. Field may have other duties, but its prime duty is to serve as "slave" of source. Conservation of source comes first; field has to adjust itself accordingly. Alternative view: Field is primary. Field takes the responsibility of seeing to it that the source obeys the conservation law. Source would not know what to do in absence of the field, and would not even exist. Source is "built" from field. Conservation of source is consequence of this construction. One model illustrating this view in an elementary context: Concept of "classical" electric charge as nothing but "electric lines of force trapped in the topology of a multiply connected space" [Weyl (1924b); Wheeler (1955); Misner and Wheeler (1957)]. On any view: Integral of source density-current over any three-dimensional region (a "cube" in simplified analysis above) equals integral of field over boundary of this region (the six faces of the cube above). No one has ever found any other way to understand the correlation between field law and conservation law. section 15 in the book "Gravitation" by Misner, Thorne, and Wheeler