Add a new page:

Special relativity is based on two postulates:

These two postulates taken together tell us that space and time are not absolute but must be relative, i.e. change depending on the observer. Otherwise, it isn't possible that different moving observers always measure exactly the same value for the speed of light. This was discovered by the famous Michelson Morley experiment.

Special relativity is Einstein’s description of how some of the basic measurable quantities of physics – time, distance, mass, energy – depend on the speed of the measuring apparatus relative to the object being studied. It shows how they must change in order to guarantee that Galileo’s principle of relativity (that the laws of physic should be the same for every experimenter, regardless of speed) should hold even at speeds near that of light.

Gravity from the Ground Up by Bernard Schutz

The best beginner Special Relativity Textbooks are:

The standard textbook is Spacetime Physics by Taylor, Wheeler

Recommended Further Reading:

Distance in Space vs. Space-Time:

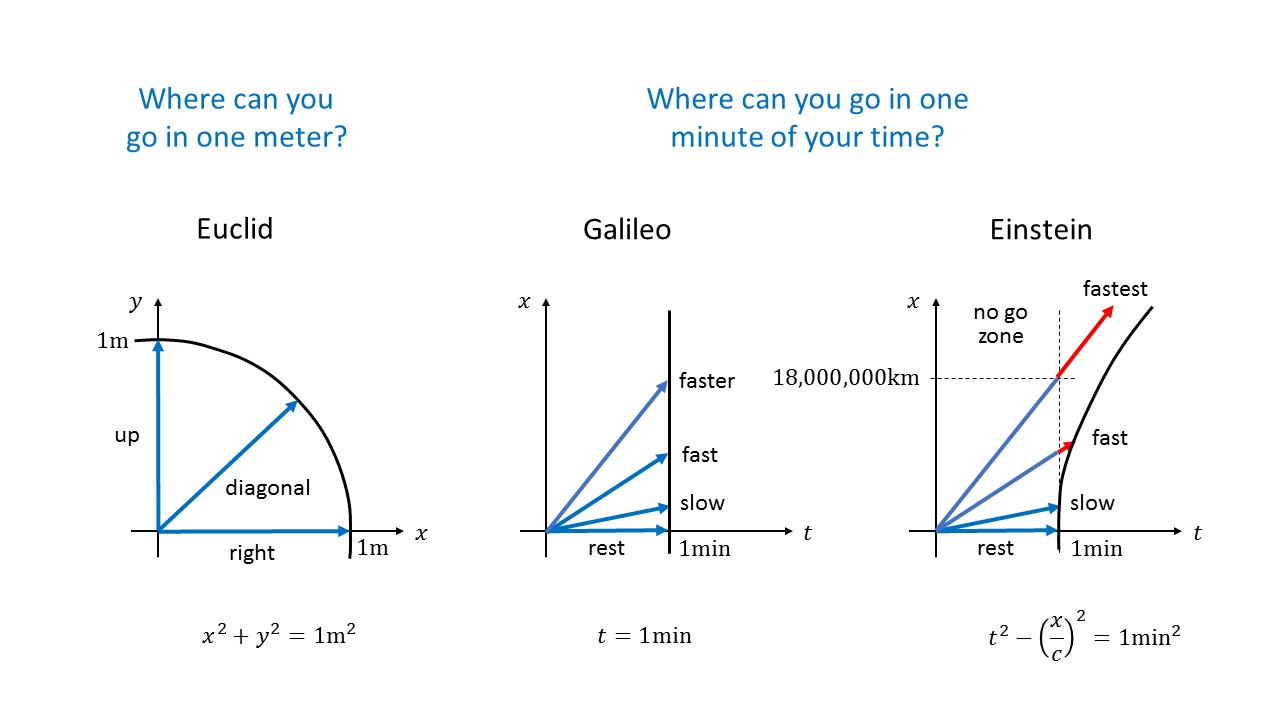

The diagram below illustrates the difference between distance in Euclidean space (left-hand side) and "distance" (actually proper time) in space-time according to Einstein's special theory of relativity (right-hand side). Time dilation is shown in red. For a more detailed explanation of this diagram see Fun with Symmetry.

Mathematically, special relativity is the statement that all laws of physics are invariant under the Poincare group.

In special relativity spacetime denotes the configuration space of a single point particle. We denote the Minkowski spacetime by $Q$, i.e., $\mathbb{R}^{3+1}\ni(x^0,\ldots,x^n)$ with the Minkowksi metric

\[ \eta_{\mu\nu} = \left( \begin{array}{ccccc} 1 & 0 & 0 & \ldots & 0 \\ 0 & -1 & 0 & \ldots & 0 \\ 0 & 0 & -1 & & 0 \\ \vdots & \vdots & & \ddots & \vdots \\ 0 & 0 & 0 & \ldots & -1 \end{array}\right). \]

Free Particle

What interests us most of the time is path of a particle \[ q:\mathbb{R}(\ni t) \longrightarrow Q \] where $t$ is a parameter for the path, not necessarily $x^0$, and not necessarily the proper time either.

To derive the equations of motion for such a free particle, we need the corresponding action \[ S(q) = \int_{t_0}^{t_1} L\Bigl(q^i(t),\dot{q}^i(t)\Bigr)\,dt \] for $q\colon [t_0,t_1]\rightarrow Q$. A useful hint towards the correct Lagrangian is that it should be independent of the arbitrary parametrization parameter $t$. The obvious candidate for the action $S$ is mass times the "proper time" \[ S = m\int_{t_0}^{t_1} \sqrt{\eta_{ij}\dot{q}^i(t)\dot{q}^j(t)}\,dt . \]

Using \begin{equation} \label{eq:relativistic-Lagrangian} L = m \sqrt{\eta_{ij}\dot{q}^i\dot{q}^j} \end{equation} and the Euler-Lagrange equations, we get \begin{align*} p_i = \frac{\partial L}{\partial\dot{q}^i} &= m\frac{\partial}{\partial\dot{q}^i}\sqrt{\eta_{ij}\dot{q}^i\dot{q}^j} \\ &= m\frac{2\eta_{ij}\dot{q}^j}{2\sqrt{\eta_{ij}\dot{q}^i\dot{q}^j}} \\ &= m\frac{\eta_{ij}\dot{q}^j}{\sqrt{\eta_{ij}\dot{q}^i\dot{q}^j}} \, = \frac{m\dot{q}_i}{|{\dot{q}}|}. \end{align*} The Euler–Lagrange equations say \[ \dot{p}_i = F_i = \frac{\partial L}{\partial q^i} = 0. \]

We can understand this better when we use the proper time as our parameter $t$ so that \[ \int_{t_0}^{t_1}|{\dot{q}}|dt = t_1-t_0, \quad \forall\,t_0,t_1 . \] This fixes the parametrization up to an additive constant. Thus $|{\dot{q}}|=1$, so that \[ p_i = m\frac{\dot{q}_i}{|{\dot{q}}|} = m\dot{q}_i \] and the Euler–Lagrange equations say \[ \dot{p}_i =0 \Rightarrow m\ddot{q}_i = 0 . \] We can therefore conclude that our free particle moves unaccelerated along a straight line.

We believe that special relativity at the present time stands as a universal theory describing the structure of a common space-time arena in which all fundamental processes take place. All the laws of physics are constrained by special relativity acting as a sort of ”super law”.

One more derivation of the Lorentz transformation by Jean-Marc Levy-Leblond

The Michelson-Morley experiment demonstrated that the speed of light is the same in all frames of reference. Special relativity is the correct theory that incorporates this curious fact of nature.

Special relativity is an extension of classical Newtonian mechanics. In particular for objects that move very fast (close to the speed of light) predictions that we get using Newtonian mechanics turn out to be wrong and only special relativity yields the correct results. For slowly moving objects both, Newtonian mechanics and special relativity yield approximately the same results.

Special relativity predicts many effects like the relativity of time or of the dilation of fast moving objects which are all in agreement with experiments. An important application of special relativity is the GPS system. Without the correct equations of special relativity, the clocks on GPS satellites wouldn't show the correct time and thus precise navigation would be impossible.

Consider the continuous motion of an object in discrete space and time, in which there is a minimum length, denoted by LU , and a minimum time interval, denoted by TU . If the object moves with a speed larger than LU TU / , then it will move more than a minimum length LU during a minimum time interval TU , and thus moving LU will correspond to a time interval shorter than TU during the motion. Since TU is the minimum time interval in discrete space and time, which means that the duration of any change cannot be shorter than TU , the motion with a speed larger than LU TU / will be prohibited. As thus, there is a maximum speed in discrete space and time, which equals to the ratio of minimum length and minimum time interval." " Now I will further argue that the maximum speed c is invariant in all inertial frames in discrete space and time. According to the principle of relativity, the discrete character of space and time, in particular the minimum time interval TU and the minimum length LU , should be the same in all inertial frames. If the minimum sizes of space and time are different in different inertial frames, then there will exist a preferred Lorentz frame. This contradicts the principle of relativity. Thus, LU TU c ≡ / will be the maximum speed in any inertial frame (see also Rindler 1977; 1991)" "In this meaning, Galileo’s relativity is a theory of relativity in continuous space and time, while Einstein’s relativity is a theory of relativity in discrete space and time.http://image.sciencenet.cn/olddata/kexue.com.cn/upload/blog/file/2010/8/20108118256119320.pdf